Aidan Dunne, essay accompanying Ellipsis exhibition by Jennifer Trouton in Millennium Court Portadown, Northern Ireland.

“In my Father’s house there are many mansions: if it were not so

I would have told you. I go to prepare a place for you.”

John 14:2

“And all the rooms they smell like diesel

And you take on the dreams of the ones who have slept there

And I’m lost in the window

And I live in the stairway

And I hang in the curtain

And I sleep in your hat…”

Tom Waits, ‘9th and Hennepin’

Once there was a man who lived in a comfortable house in Belfast. He was a member of the Presbyterian Church and he believed in the primacy of God, the authority of scripture and the importance of studying the Bible and living according to its precepts. Faith was not something purely internal or academic

but should be manifested in everyday life. It was not enough for him to feel virtuous, for he knew that true virtue resides in actions and that one must strive to be generous and considerate.

During his youth, he was never quite sure what he wanted to do with his life. He was good with solid and mechanical things, and he applied himself to learning more about them, acquiring skills and finding employment in the industrial, industrious city. He enjoyed feeling that he had a role in society, that he was in some way part of a great co-operative venture. But the society he lived in was more and more prey to tensions and discord. Also, he still felt partly unfulfilled, as though he knew in his heart that there had to be more.

A practical man, easily equal to the problems posed by the material world, problems that could be solved by the application of measurement and calculation, common sense and craftsmanship, he became reflective. He dwelt increasingly on abstractions, studying scripture and its theological interpretations. And he began to think about his own past, about his childhood, his family and the history that had shaped them.

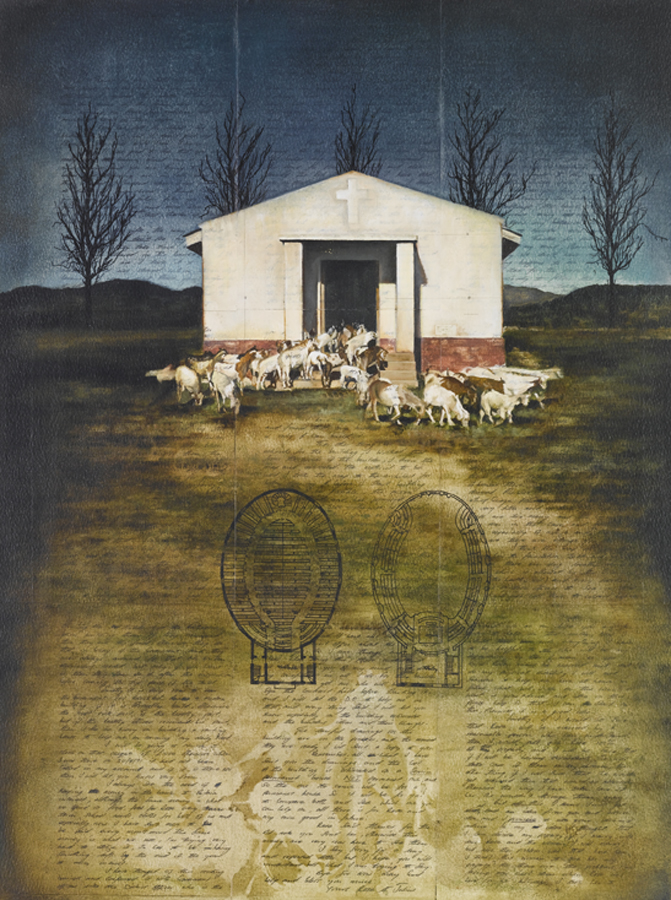

When the opportunity arose, he suddenly knew that he should embark on missionary work in Sudan in Africa. It was another world, and in this world he found that he could rediscover his sense of purpose, that he could make a difference. He could serve God and his neighbour too, and neither got the lesser part of the bargain. Life was vivid and direct. His practical skills served his spiritual aspirations. He knew what had to be done and he was able to do it. He was, it seemed to him more than once, happy, fulfilled.

Later, settled back in his house in Belfast, a house where he had spent so many years of his life, Africa often seemed like a strange and wonderful dream.

Engaged in some ordinary task – he might be painting a doorframe, or laying the table for tea – he would pause and recall, as vividly as if it were happening

in front of him, a scene bathed in the brilliant light and heat of that other continent. His memories of Africa were a living presence in his home.

While there he had come into contact with a young man who cared devotedly for his younger, infirm sister. Brother and sister became the focus of his efforts at

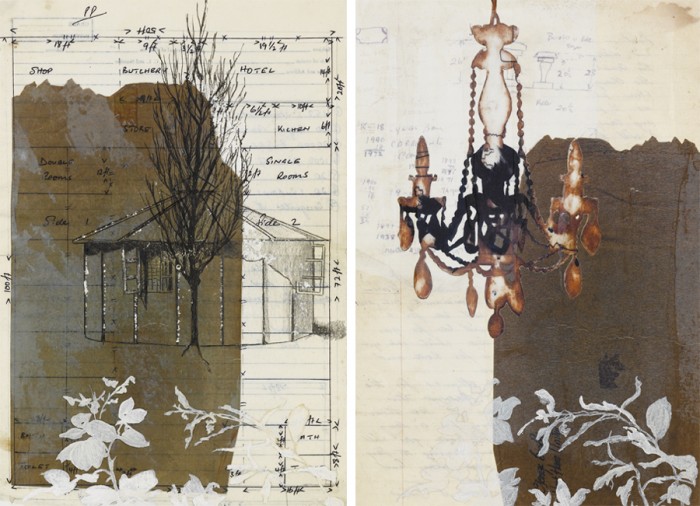

practical generosity. They exchanged letters regularly. He thought about what he might do for them. Eventually he resolved to have a house built for them, one that would be carefully attentive to their needs. Planning every detail with the utmost care, in his own house he made drawings and notes in preparation for another, imaginary house. In time, that imagined house became a real house, a real home.

Years went by. He noticed that his own home, a repository of so many personal memories,had accumulated a tangible history of its own – he could measure it in its successive layers of redecoration and alteration, the details of which were recorded in his notebooks and even on the backs of envelopes. He mused on the past, the distant past of his childhood and the more recent, African past, and he studied the Bible and thought about the links between all these things. At times he seemed to be on the verge of reaching some definitive conclusion but always, in the end, it remained elusive. Still, he clung to one overriding truth, knowing that, in building a house in Africa, he had lived his faith.

Jennifer Trouton’s paintings in Ellipses don’t really tell a story in any conventional sense of the term, and you could say that the foregoing is one of the stories that they don’t tell. Nowhere do they sketch out one complete, linear narrative as such. At the same time, they are infused with a wealth of potential stories, and the one related here is just one of them. It pertains to universal concerns, to our search for meaning in life, our need to belong to a family, a community, an ethos, the possibilities open to us for making things better, the inexorable transience of life and the stark limitations that govern human existence. All of this is visualized within the framework of a single domestic space and the tangible and intangible ways it accrues evidence of lives lived within it: “the dreams of the ones who have slept there.”

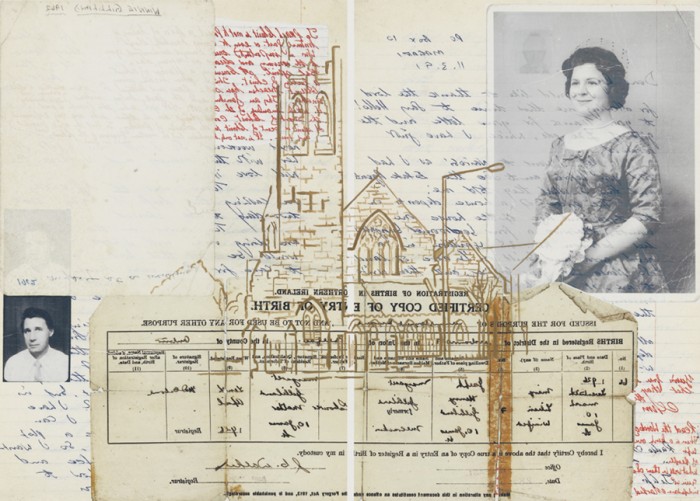

When Trouton moved into her present home, she and her partner found themselves engaged in the kind of domestic archaeology that goes with establishing yourself in a place that was previously occupied. Various factors had conspired to ensure that their house was richly stocked with traces of the person who had lived there before. In clearing out rooms and stripping wallpaper, she found herself dealing with poignant, intimate reminders of another consciousness, the fragmentary record of someone dealing, as everyone must, with the standard complexities of life.

She began to archive and document this material throughout the process of renovation and change. But her aim was never that of an historian or an archaeologist. Not, that is, to reconstruct a coherent picture of what once was, on the basis of surviving evidence. What interested her most was the way aspects of our personal histories are written into and even illustrated by the spaces we occupy. Her interest was certainly enhanced by the fact that all the evidence suggested that her predecessor was himself engaged in the project of trying to make sense of his personal world based on a mass of piecemeal evidence. As Tolstoy observes in Anna Karenina, from the internal, individual perspective, everybody’s life seems hopelessly chaotic.

It is hardly surprising that our homes should be idiosyncratic personal spaces. People invariably set out to personalize the spaces they occupy, but something much more 3 Aidan Dunne, essay accompanying Ellipsis than decoration or embellishment is at issue. Gaston Bachelard’s celebrated The Poetics of Space, originally published in French in 1957, is probably the most famous text dedicated to exploring a phenomenological approach to architecture. Rather than

looking at architectural space in terms of its relationship to its stylistic precursors, and at the history of architecture as a chronicle of successive styles, the phenomenological approach puts the human experience of architecture at the centre of the picture.

Throughout the 20th century many architects and architectural theorists and historians substantially changed the way we look at and make buildings based on this shift to a phenomenological perspective (though arguably not half enough). In this context Bachelard was actually something of a conservative, resistant to Modernist ideas. His ideal domestic space, for example, is a substantial house of a kind unavailable to the vast majority of the population. Yet he displays an extraordinary grasp of the importance of space in ways far removed from conventional functional definitions.

He devotes a great deal of attention to spaces in literary fiction, elaborating on such apparently peripheral details as drawers, corners, attics and cellars. Oddly enough it is because he was an historian of science that the concept of reverie became central to his way of considering spaces. In his view, the provision of a space for drifting or day-dreaming is essential to the emergence of scientific rationality and for all creative activity, precisely because such a space offers the possibility of transcending the given order of things, of overcoming the epistemological obstacles that mire us in a fixed view of the universe. Our favourite spaces, it seems, are sites of reverie, places where our imaginations are set free.

In Trouton’s work it is as if the fabric of the house’s internal spaces are animated by the consciousness of the person who dwelt there. The seams that join sheets of wallpaper feature subtly but insistently. Yet the intact, impassive surface that they usually signify is pierced and sundered in various ways, whether peeled back or rendered transparent to reveal overlapping layers of once hidden images, snapshots and mementoes of other times and places, Africa in Belfast, handwritten notes, schematic drawings, all in the context of bricks and mortar. What we see are fragmentary traces, glimpses, the products of a trawl through a lifetime’s memories and reflections, necessarily inconclusive, elliptical and open-ended.

A chandelier blazes with light and fades so that it is only a ghostly impression. In other paintings, living vegetation is juxtaposed with the fixed patterns derived from it, the flux of life stilled and consigned to the past. Repeat patterns in themselves suggest the rituals and routines marked off on the calendar. There is no question but that we are dealing with the past, with things lost, and there is a certain elegiac quality to the body of work as a whole. Yet time past is also redeemed through dreamlike recall, transcending any simple chronological record of events. Bachelard’s oneiric spaces, after all, bear a striking similarity to another privileged space apart: the artist’s studio, where magic happens.

Aidan Dunne

Chief Critic, The Irish Times